Bankers, this is the price of lacklustre cybersecurity (Part 1)

You’re gambling more than just money.

Over 9 billion data records were lost due to negligence or stolen by cybercriminals since 2013. Worse, more than 1.9 billion records—or 10.5 million per day—have been compromised just from January to June this year. The information gold mine that it is, the financial services industry wasn’t at all safe from cyberthreats. During the first half of the year, BFSIs saw 125 data breaches or 14% of the total attacks worldwide. But the statistics don’t end there. Five million records were also lost, a 389% increase versus the previous biannual cycle. As the financial landscape becomes more and more digitised, BFSIs can only expect even more relentless breaches.

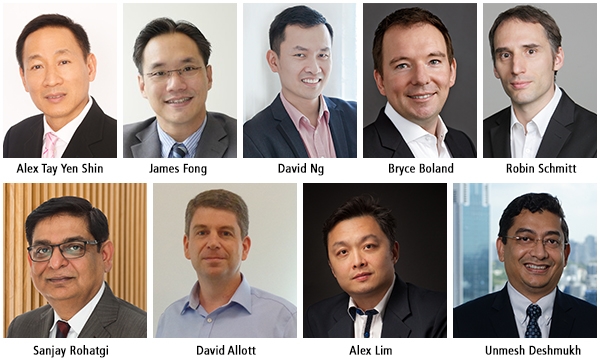

“The financial services industry remains a popular target for cyberattacks,” says Alex Tay Yen Shin, ASEAN regional director, enterprise, and cybersecurity of Gemalto. He adds that “Today, data is the new oil and cybercriminals are cashing in on it.” Factors such as outdated security protocols and legacy back-end systems, on top of being a massive data pool, serve as further incentives for cybercriminals to target BFSIs.

In fact, James Fong, RSA Archer Solution Leader, governance, risk, and compliance for Asia Pacific and Japan, even puts BFSIs as 300% more likely to encounter cybersecurity incidents compared to other industries. Whilst stronger security measures follow suit, “…that has not stopped money-hungry cybercriminals from continuing to hack away at banks and financial firms’ defences,” explains Fong.

The threats are significantly more pronounced in Asia. Bryce Boland, chief technology officer, Asia Pacific, FireEye Inc., expresses “Asian countries are significantly less aware of the threats posed by technology than other regions. Few of the major breaches we see in Asia are ever reported publicly, and as a result many people think this issue isn’t as bad here. However the opposite is true.” He also mentions that organisations in Asia are twice as likely to be targeted as ones in the US.

Besides awareness, Boland notes that the global shortage of skilled cybersecurity professionals also contributes to the threat landscape. “Many economies in Asia struggle to develop cybersecurity talent, and lose the rare talent they have to higher paying economies, or to major security vendors who can offer the best opportunity to learn.”

Due to these factors, among others, banks in regions like ASEAN and APAC are huge heat magnets for cybercriminals. David Ng, Trend Micro lead for FSI and EDU, says that an INTERPOL-led cybersecurity operation earlier this year uncovered that 8,800 servers throughout ASEAN targeted BFSIs via attack vectors like ransomware, DDoS, and spear phishing. Solely for the APAC region, malware detections during the first half of the year peaked at 436 million, with Business Email Compromise (BEC) attacks being very common amongst BFSIs. Further zooming into Singapore, the city-state’s financial, insurance, and real estate sector had one in every 202 emails containing malware.

Robin Schmitt, general manager APAC for Neustar, says that whilst the cyber race has both attackers and defenders trying to outflank each other, the former seems to be one step ahead of the latter. Indeed, there’s a multitude of cyberattack strategies being employed nowadays.

David Allott, McAfee cyberdefence director for APAC, cites ransomware with worm-like capabilities, Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs), zero-day exploits, and even primary cyberattacks being used as a smokescreen for another as just some of the newest cyberthreats lurking in the landscape. Moreover, no devices are safe as Windows and MacOS devices, smartphones, and wearables are being equally exploited for criminal activities. Schmitt adds that another popular means of attack were massive botnets. Ran by IoT devices, these networks were used for volumetric DDoS attacks on a scale never seen before.

“Now that all kinds of devices and operating systems can connect to enterprise applications and access data, increased visibility is tantamount,” notes Allott. With sensitive information like credit card details and bank account information nowadays living in consumers’ phones, additional security measures become even more of a necessity.

“If banks overlook the importance of endpoint security, they open not only their customers up to risk, but also themselves as well,” Alott adds.

And as the industry further digitises, so too does the surface attack area widens. “As we had predicted in 2015, we saw an increase in attacks against corporations and financial institutions themselves during 2016,” says Sanjay Rohatgi, senior vice president of Symantec Asia Pacific and Japan. “Financial institutions are confronted with attacks on multiple fronts. The main two types are attacks against their customers and attacks against their own infrastructure.”

The digitisation of finance brings with it conveniences such as e-payments and on-the-go banking. But whilst there’s added value for customers, there’s also an increased risk for cyberattacks. If there are any weaknesses in a bank’s defence strategies, these attack verticals can easily spread through to the backend systems.

Alex Lim, Forcepoint SEA regional sales director, adds that the rise of fintech and cloud adoption has rendered it increasingly difficult to secure critical business data. Now, sensitive data isn’t solely in a bank’s data centre; rather, it’s now everywhere. “In fact, 95 percent of organisations are running either cloud apps or infrastructure-as-a-service today. And for those applications that aren’t in public cloud, enterprises are using the same technical approaches utilising private clouds.”

Further making things complicated is the use of mobile platforms and the BYOD phenomenon. Lim says that 67% of the workforce use their own devices at work today, and by 2020, 42% of the global workforce computing will be done on mobile—further increasing the chance for data breaches.

“The perimeter has simply changed. It’s no longer defined by the boundaries around the data centre, the in-house network versus the Internet. It’s just not that simple now: users and critical data are everywhere. Essentially, we’re living in the time of the ‘zero-perimeter.’”

Traditional bank cyberdefences are made for the periphery, such as firewalls, anti-viruses, content filters, and intrusion and detection solutions, with the purpose of keeping attacks out of the system. Shin mentions that there is little banks can do to stop threat actors once they’ve bypassed the frontline security measures. “Therefore, it has become apparent that relying on perimeter security alone is no longer sufficient.”

Schmitt also observes that “The defence approaches of many FSIs are still stuck in the passive mode, with most resources channelled into remediation efforts rather than proactive prevention strategies.” Shin agrees, saying that cybersecurity now demands a modern, data-centric approach, as opposed to one that’s designed to keep threat actors out.

In this zero-perimeter world, Lim suggests the need to go back and protect the human factor. Though it’s the point where man and critical data intersect and provide value to both banks and clients, it’s also the most vulnerable to malicious and criminal acts. Shin also explains that current cybersecurity strategies are starting to look inwards to focus more on data protection. He highlights three general steps for better internal security.

First, organisations need to accurately identify exactly where their important data are, who has access to these data, and how access is being managed. Next, data encryption and multi-factor authentication for both employees and customers should be standardised. Lastly, encryption keys need to be carefully handled, including the ability to generate, distribute, store, rotate, and revoke or destroy the cryptographic keys. The presence of encryption keys not only make garbled data useless to criminals, it also limits the data accessible to any one person.

However, only 4% of recent data breaches were secure breaches, that is, involving encrypted data. Though the percentage is miniscule, Shin explains the advantage of such cases as “Even though the attacks couldn’t be stopped, at least no personal or financial information was misused in the end.”

Unmesh Deshmukh, Akamai Technologies Asia Pacific and Japan regional vice president for cloud security, also highlights the importance of safeguarding Application Programming Interfaces (APIs). Whilst necessary for customer-centric services and fintechs, APIs can also serve as side doors that hackers use for attacks such as data breaches, fraud, or making banking services unavailable. “Whilst APIs are critical in enabling the delivery of a great online experience, protecting APIs from attacks and security breaches is non-negotiable,” he explains.

Another cyberdefence oversight that banks often have is the existence of too many pieces of security software. Whilst on the surface it seems like more security equals better security, Allott countered that these will create information silos that can paralyse entire systems. More often than not, these silos are some of the highest liability points in an enterprise infrastructure as they can reveal weak links in the security chain.

But criminals don’t just rely purely on sophisticated and complex computing attacks. According to Rohatgi, they also mimic customer behaviour and use social engineering—paired with mobile malware to steal transaction authentication credentials—to trick financial institutions.

Likewise, threats aren’t just plain hackers. There are hacktivists, cybercriminals, and yes, even nationstates. "The hacktivists often get airtime, but usually cause the least real damage. The cybercriminals are entirely motivated by greed,” explains Boland. Of the lot, nationstates are the most dangerous. They can spend years pilfering huge amounts of data in the background, with the purpose of using said intelligence for various economic, political, and military objectives.

Should BFSIs choose to ignore all these threats and breach factors, what’s the worst that could happen? Deshmukh warns, “The exposure to mass fraud or service unavailability could potentially have an irreversible impact on brand image in addition to revenue loss, fines, and penalties imposed by regulators.”

That’s just the tip of the iceberg though. Successful cyberattacks have long-lasting consequences for every party involved; some even causing institutions and their top brass to bow out of the game.

Advertise

Advertise